Social Cohesion in New Zealand: How Policy Relates An Update On My PhD Journey

Do we have shared values? Join me as I unpack the role of policy, identity, and politics in shaping social cohesion in New Zealand today.

From full-time hustle to full-time PhD: My journey so far

The past nine months of my PhD at Te Herenga Waka School of Government have been a whirlwind of research, reflection, rest, and recovery. It’s the first time I haven’t been juggling full-time work with part-time study, and honestly, focusing on just one thing feels almost like a holiday.

I’ve been treating my PhD like a full-time job. Every day, I head to Level One at Pipitea Campus and am surrounded by other PhD students researching management, information systems, and economics. Being in this environment has allowed me to dive deep into my research on social cohesion and policy in New Zealand.

With the support of my two PhD supervisors: Michael Macaulay and Wonhyuk Cho, who have been incredibly supportive. I’ve written two book chapters for book that will be published in the next year, I have started to learn how to write grant applications, which I have found surprisingly exciting. I have also supported the academic staff as a research assistant and tutor for public policy papers.

While applying for these grants, I've been lucky to meet and engage with senior academics like Markus Luczak-Roesch, Arthur Grimes and Anna Matheson. A positive outcome of meeting these wonderful people was learning about and deciding to apply to Te Pūnaha Matatini as an early career researcher. And I am thrilled to share that I've been accepted as part of the Te Pūnaha Matatini whānau.

Why I’m doing this PhD

Pursuing a PhD was a deliberate decision to step back from the career race and invest in deep, meaningful research. It’s been an incredible experience that has already yielded insights I couldn’t have imagined when I first started. My goals remain clear:

Learning to conduct innovative and high quality research.

Deepening my understanding of policy and social cohesion.

Finding clarity about what I want to do for the rest of my career.

So today, I thought I'd share some of the things I’ve learned about social cohesion in New Zealand since I started in January 2024.

Why social cohesion matters

At its core and in its simplest forms, social cohesion is the absence of violence, and I think we take it for granted. I also think we misuse and overuse the term. New Zealand’s social cohesion has long been a point of pride and a key factor in our ability to live in relative harmony across diverse communities. But things have changed.

We’re now hyper-diverse, our ideas of what we want and how to get there are not just different, they are competing. Our political landscape is more fragmented, emerging technologies, our ageing, growing and diverse population is protected to fracture us further and questions about what really holds us together are getting louder—and, honestly, scarier.

At the heart of my research is a big question: Can our current understanding of social cohesion, rooted in outdated and overly romanticized frameworks, still guide us in a society that has dramatically evolved since those frameworks were first developed? And what role does policy play in this critical evolution of our capacity to coexist?

Did you Know we’re using a social cohesion definition from 1988? This is No bueno.

New Zealand’s current approach to social cohesion is based on a framework designed in 2005 by Professor Paul Spoonley. This framework was adapted from a Canadian model from—wait for it—1988. This framework has been reaffirmed over the years, most recently by the Royal Commission of Inquiry after the Christchurch attacks in 2020.

Here is the definition currently used by the MSD Social Cohesion framework:

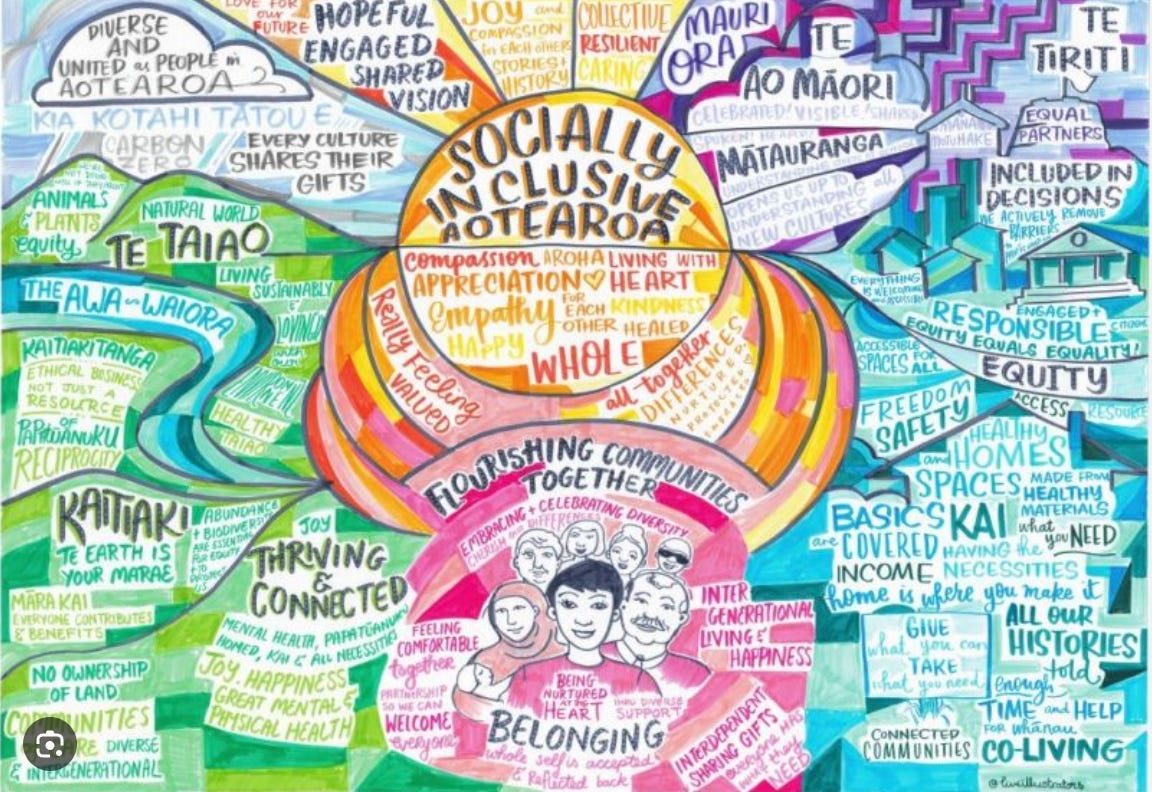

In 2021, Cabinet agreed in principle to all of the RCOI recommendations, including those related to social cohesion. Cabinet endorsed the definition of social cohesion used by the RCOI. This definition, developed by Professor Paul Spoonley, Robin Peace, Andrew Butcher and Damian O’Neill, describes social cohesion as a sense of belonging, participation, recognition, legitimacy and inclusion. The report noted that social cohesion exists where people feel part of society, family and personal relationships are strong, differences among people are respected, and people feel safe and supported by others. Social cohesion was described as an ideal rather than a goal to be achieved and something that must continually be nurtured and grown.1

I was lucky enough to be part of the team that developed that definition and work, and it spiked mi interest and obsession with this idea of social cohesion. What I came out thinking after that work, and the long engagement process we ran across the county with very different groups and views is that we no longer have shared views, values or can agree on how to get to the ones we do share. Governing seems like an impossible task, that no matter what step anybody takes, it further divides us all. The way we use social cohesion is romanticies, overused and misused constaly. For example, do you know who else has a strong sense of belonging, trust, and shared values? Organised crime groups, both here in New Zealand and overseas.

So, it’s time to get real about what we mean when discussing social cohesion. How can we use it to develop policies and have meaningful debates that recognise we’re right not to have universally shared values? How can we all coexist, and what kind of policies do we need to acknowledge that?

Our ‘shared values’ are a hot mess of contradictions

While some groups still hold on to inclusive and tolerant values, others cling to more traditional ideas of being a New Zealander. For some, being a “real New Zealander” means being born here or having New Zealand or Māori ancestry. For others, identity is more about feeling like a New Zealander, having lived here for some time or even just having a passport, regardless of whether you have lived here or not2.

But even within these groups, there are contradictions—especially regarding who gets to participate in discussions around issues involving Māori and the Crown. These conversations often become binary and exclusionary, leaving overseas-born New Zealand citizens—especially those from marginalised or oppressed backgrounds—unsure of where they fit. Are they Pākehā (being defined as all Non-Māori), Tangata Tiriti, or Tauiwi of colour or just immigrants wanting to have a better life? Even if they know where they stand, have high literacy around Māori history, tikanga and reo, their participation ability is often limited because they don’t whakapapa back to Aotearoa or fit neatly in any of these definitions.

When you dig into the data, these contradictions become glaringly obvious. But they stay hidden because they’re buried in obscure research and sugar-coated with a romanticised narrative that was developed in 1988 in Canada about having a sense of belonging. Honestly, it doesn’t hold up anymore. Shit is just not that simple.

Our policies are outdated and oversimplify this complex term

The idea that all New Zealanders share the same core values simply doesn’t match reality anymore. Different groups value either inclusive civic responsibilities or exclusive inherited traits, leading to a fragmented national identity. This raises tough questions about whether policies based on universal civic values can still work in a society where those values are no longer shared.The tension between groups prioritising inclusivity and those clinging to exclusivity forces us to ask: Can our current policies unite us, or are they too out of step with reality?

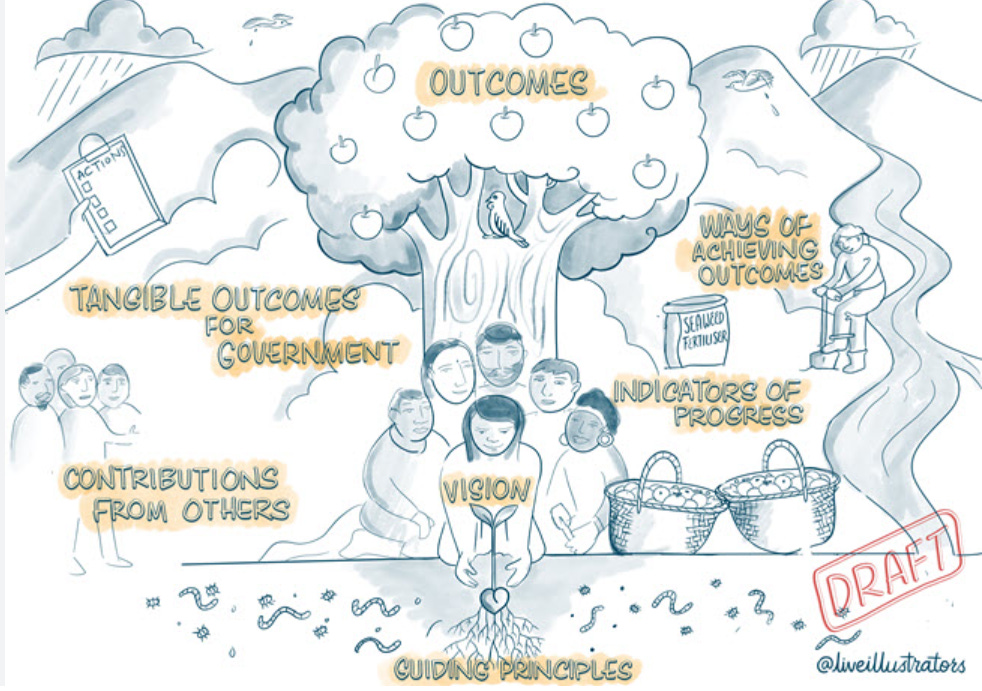

I think that we need a definition that recognizes that there are different types of social cohesion like for example, strong and weak social cohesion, positive and negative social cohesion, social cohesion at the neighbourhood level (micro-level), social cohesion at the communities level (messo-level) and social cohesion at the national level (macro-level). I think we need to consider the social cohesion that online groups have and what impact hey have on neighbourhood or national level of social cohesion.

I think we need a clear distinction between the ideas of social cohesion, social capital and welling. You might think the differences in definition and indicators for each term ar obvious, but believe me when I tell you they are not. Some research believes social cohesion is a sub-section of social capital, some research assume social cohesion is always positive, some research recognizes that it is more complex than that. I can go all day and in another post Ill do a summary what I have found in the literature, but for now just trust me when I say, its messy.

Can housing policy help us coexist? The honest answer is I don’t know and apparently neither does the government.

Here’s the truth: I don’t know if housing policy can fix our social cohesion challenges, and neither does the government—or most academics, for that matter.

There’s plenty of research on housing policy and social cohesion, but the connection between the two is often tenuous at best and non-existent at worst. Government frameworks mention housing in vague terms like “place,” “tūrangawaewae” and “neighbourhoods,” but they miss the opportunity to directly link housing policy with robust broader social cohesion frameworks.

The Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has a vision: "Everyone in New Zealand lives in a home and a community that meets their needs and aspirations." However, a recent OIA response revealed that HUD doesn’t explicitly use social cohesion as a guiding framework. Instead, they rely on strategies like the Government Policy Statement on Housing and Urban Development (GPS-HUD) and MAIHI Ka Ora, the National Māori Housing Strategy. While these initiatives aim to tackle housing issues, the lack of focus on social cohesion raises questions about whether our housing policies can enable us to co-exist within our different and competing views.

So, we’re diverse. Now, how do we unite?

We’ve done much work recognising our differences, but how do we find enough common ground to hold society together? Our population is divided into so many groups and sub-gruops that governing effectively has become a real challenge. The key question is: How do we respect everyone’s individuality while still finding a way that allows us to coexist and function as a unified country?

New Zealand’s 2023 Census was translated into over 25 languages3, which is great for accessibility, something I am a huge advocate for, but it creates an unrealistic expectation that all policies must be translated into 29 languages. That is expensive, time-costing and a totally unrealistic expectation for government to do. This is an extreme example, but I share it to make a point. Balancing hyper-diversity with enough common ground to build functional communities is a massive challenge.

It’s time to rethink what it is and how we achieve Social Cohesion

Reimagining social cohesion and being more deliberately on how policy can influence it

As New Zealand grapples with growing diversity and political polarisation, the need to rethink what holds us together has never been more urgent. My research argues that if we continue relying on outdated models and assumptions, we risk missing the opportunity to build a genuinely cohesive society. We need policies that acknowledge our differences while fostering enough common ground to sustain collective action and trust.

In a world increasingly defined by division, can New Zealand lead the way in finding new paths to social cohesion? I believe we can, but only if we’re willing to confront uncomfortable truths about privilege, identity, and the limits of our current frameworks.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on these issues. Should we be paying more attention to the links between housing policy and social cohesion? And what does social cohesion even mean to you in today’s New Zealand?

If you enjoyed this deep dive, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support allows me to continue exploring these critical topics every week.

Catch you next Tuesday!

Te Korowai Whetū Social Cohesion tools and resources - Ministry of Social Development (msd.govt.nz)

Humpage, L., & Greaves, L. (2017). “Truly being a New Zealander”: ascriptive versus civic views of national identity. Political Science, 69(3), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/00323187.2017.1418177

2023 Census – It is about all of us | Stats NZ

Mmm. It is certainly a sad state we are in. I think a large part of the problem has immersed with all this focus on "identity". We have analyzed and broken society down into 'groups' and 'sub-groups' for so many years that now most people feel they identify with/as something or another. Be it political, racial, economic class, career status etc. When in reality, each human being, left alone without this external peppering of 'definitions' is able to be an agent of rolling ideas and perspectives relative only to the events of the day. Free to be individuals who use 'discernment' rather than group think. That's the psychological element of the problem with our lack of cohesion in my view. The physical contributor is the luxury of our times. The tech world is advanced, we embrace the physical "easy". I live in a valley where in the 1920's there was a make-shift township of 1200 people building a 100km railway line through steep hill-country. The men were digging tunnels with shovels all day. The women were raising children, lighting fires and cooking. There was a light bulb in each hut and one tap with cold water for every ten working families. The stories from the time are just gorgeous, real community, sport games and school events. The reality is, they didn't have the luxury of not taking care of their neighbour's needs, everyone needed the support of the others and they relied on it. I guess a degree of hardship can sort out our hearts. What is true and good and real is again put into perspective in times of shared struggle, where survival and celebration of the small joys are the focus. There was also no one writing stories about how everyone should "identify" or what "group" they could pigeon hole themselves into. These modern ideas of the privileged and non-privileged set off a toxic bomb and foster either a sense of guilt or a sense of victimhood and entitlement. Those seeds of misery. I don't have the answer either. Except to say that if we took the internet and newspapers away tomorrow, all this division would most likely fade away back into a sense of community. It is important to teach our young people that they do not have to identify as anything. They are more than entitled to be shifting, changing, growing, developing learning beings for the rest of their lives without a label on their forehead or back. To wake up brand new each day. When it comes to racial division... we should just stop talking about race. It is not the most important thing about a person. As Martin Luther King said.... its "the content of our character." Our actions define our character, its in 'what' we 'do'. If we don't feed the homeless, care for our old, protect our children or treat each other as equals, then we are surely lost. Too much focus on 'identity' leads to an excess of pride, which fosters narcistic self-righteousness. We are all equals. We need to again foster this idea. It starts with the government and the media and it must be taught in the home. Thanks for firing my brain up this morning Natalia. I share your deep concerns and hold a large sadness for the unfortunate state of our human family.

Diversity is a challenge to social cohesion. We are built to ‘cohere’ with people like us. The best outcome, if diversity leads the way, is a state that mechanically maintains the rules that all groups get to play by.