The Accountability Void in New Zealand’s Public Service

New Zealand’s public service wields enormous power, yet the perception is that those at the top are rarely held accountable. When things go wrong, the system protects itself—not the public.

Last week, I wrote about why I oppose the four-year parliamentary term proposal. My argument was simple: our accountability mechanisms are already weak and giving politicians more time in office without fixing that is a mistake. But accountability issues don’t stop with publicly elected officials—they run even deeper within the public service itself. If you think it’s hard to hold MPs accountable, try holding unelected bureaucrats to account.

The Bureaucratic Wall

New Zealand’s public service is run by people we don’t elect. Inside the sector, they’re categorized as Tier 1 (Chief Executives), Tier 2 (Deputy Chief Executives), and Tier 3 (Directors and General Managers). These are the people who shape policy, manage billion-dollar budgets, arm wrestle and advise with Ministers on how to spend public money and govern the country. They also make a lot of unilateral decisions—the so-called operational matters that don’t require ministerial approval but can have just as much impact on the country.

I’m not a public administration or public management expert—I see the New Zealand public service as political institutions, not just bureaucratic ones. That perspective comes from both over a decade of working inside the system and my master’s research on how the “institutional will” becomes the “institutional wall”—how good intentions inside the public service often end up reinforcing the very barriers they claim to dismantle.

When the public service fails, underperforms, or engages in misconduct, the consequences are often even weaker than in politics. No one gets voted out. No one is publicly scrutinized the way MPs are. Bad leadership decisions rarely lead to repercussions, and when things go wrong, the instinct isn’t to fix the system—it’s to protect the institution and the senior officials who represent it. Sure, you can OIA them, but as my master’s research showed there are also ways around that, so you don’t get the exact information you need. The OIA is a whole other topic, so let’s just assume that while the OIA has a place and I am a big fan, it’s out of scope for this particular Substack article.

The Public Service Act 2020: A Weak Accountability Framework

On paper, the Public Service Act 2020 establishes a framework for holding Chief Executives accountable. It outlines clear performance expectations, sets fixed-term contracts (usually five years), and gives the Public Service Commissioner the authority to review performance and, in theory, recommend removal if a Chief Executive isn’t meeting expectations. But the real power to dismiss a Chief Executive rests with the Governor-General, acting on the advice of the Commissioner and the Minister for the Public Service. This structure means that, in practice, the removal of a Chief Executive is an extremely rare event, usually handled quietly rather than as a public accountability measure. So whatever the Public Service Act 2020 says, it’s ineffective in demonstrating any sense of accountability for the leadership group of the public service.

So while the Act gives formal oversight powers to the Commissioner, the reality is that poor performance, mismanagement, or even misconduct rarely lead to serious consequences. Instead of outright dismissals, underperforming Chief Executives are more often moved sideways into new roles or quietly exit with little public scrutiny. There is no real transparency in how performance is evaluated or how often concerns raised internally actually lead to action. Unlike MPs, bureaucrats never have to face voters, and their careers are shaped more by internal networks and relationships than by public scrutiny or public expectations.

This lack of meaningful and effective accountability extends beyond individual leadership failures. The Francis Report (2019) exposed a deeply ingrained culture of bullying and harassment inside Parliament, showing that staff feared retaliation, that internal complaints processes were ineffective, and that institutions were more focused on protecting their reputations than addressing harm. But here’s the issue—no similar investigation has ever been done into the wider public service. If these failures were rampant in Parliament, a highly visible and scrutinized institution, what does that say about a bureaucracy that operates with even less public oversight?

This isn’t just an academic debate—it has real-world consequences. The Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Christchurch terrorist attack made it explicitly clear that a lack of diversity in leadership within the public service was a major concern. And that lack of diversity is directly tied to ineffective accountability mechanisms at the top. The report found that many government agencies lacked the cultural competency and leadership diversity needed to effectively engage with the communities they serve. It highlighted that before the attack, there had been limited national dialogue on how to uphold New Zealand’s bicultural foundations while embracing its growing multicultural population. This lack of engagement wasn’t just an oversight—it contributed to blind spots in national security, community relations, and policymaking that failed to protect the people most at risk.

The Public Service Act 2020 was supposed to improve public sector leadership, but it doesn’t address these structural inequalities. Instead, we’re left with a system where leaders are insulated from real consequences, diversity is treated as a secondary priority, and accountability mechanisms are too weak to drive meaningful change.

Lack of Accountability: A System That Protects Itself

When I was researching my master’s thesis, I sent an OIA with 33 questions to 17 government agencies. Amongst my questions I asked: How do you know you’re not discriminating internally? Their answer? Because the Code of Conduct says you can’t. I asked them how they knew their Chief Executives and Deputy Chief Executives weren’t discriminating. Their answer? Because the Code of Conduct says they shouldn’t, and because they haven’t received any formal complaints. My aim was to put the burden of proof of discrimination on the institution and away from the victim, as an academic experiment.

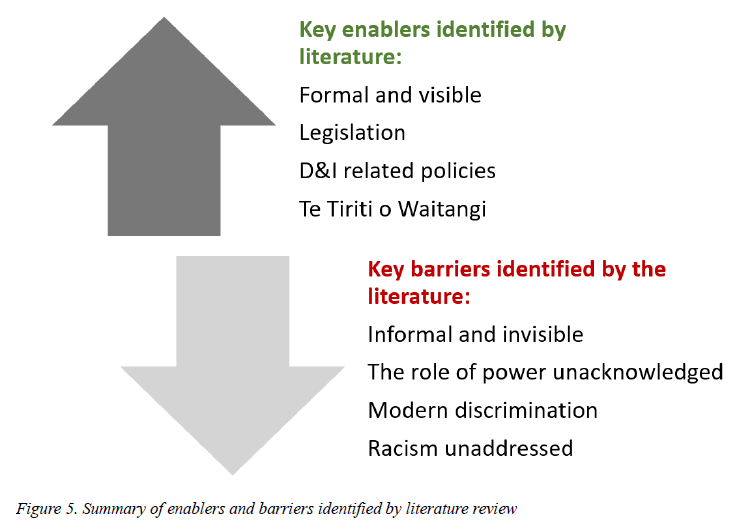

This figure above highlights the gap between formal mechanisms (such as legislation, diversity policies, and Te Tiriti o Waitangi) that are intended to enable equity and diversity within leadership, and informal barriers (such as unacknowledged power dynamics, modern discrimination1, and systemic racism) that continue to obstruct meaningful progress. While enablers exist on paper, systemic and cultural barriers remain largely unaddressed becase they are invisible and hard to identify and measure, limiting real change in leadership diversity and therefore in accountability.

Their answers to my OIA were the kind of reasoning that isn’t just weak, but a complete failure of accountability. A policy sitting on a shelf doesn’t prevent discrimination. A lack of formal complaints doesn’t mean discrimination isn’t happening. What it really means is that the internal complaints process is so ineffective, so stacked against employees, that speaking up isn’t worth the risk. My research showed that across a workforce of over 28,000 public servants, only 13 formal complaints were raised per year. That’s 0.2%—a statistical impossibility if the system were actually working.

The Speak Up Framework, which was supposed to make it easier for public servants to report wrongdoing, has instead become another tool of institutional self-preservation and should be called the Shut-Up Framework. Employees who file complaints face career consequences, while those in leadership remain shielded by bureaucratic process. The Francis Report (2019) made it clear that in Parliament, a culture of bullying and harassment flourished because staff knew there were no real consequences for those at the top. The same dynamic exists in the wider public service, except with even less scrutiny.

The public service prides itself on being neutral and evidence-based, but there’s shockingly little evidence that its own internal structures are functioning as intended. When power is concentrated in a homogenous leadership class, accountability isn’t just weak—it’s almost nonexistent. And that’s a problem that no amount of bureaucratic restructuring, glossy policy frameworks, or DEI buzzwords can fix.

[If you want to follow a public service expert, that describes every week on her Substack way better than I can, follow Bowl of Fish Hooks, link below.]

So while politicians may be pushing for longer terms under the guise of “efficiency,” we should be asking a different question: why are we not demanding real accountability from those who run the public service, too?

Why DEI Policies Don’t Work - and Why That’s Not an Argument for Scrapping Them

While we are on the diversity and inclusion policy space, lets discuss Winston Peters and Donald Trump wanting to scrap DEI policies entirely, and in some ways, I agree with them—just not for the same reasons.

My research and my experience, both as a public servant navigating the system and as a manager responsible for diverse teams, have led me to conclude that DEI policies in their current form are ineffective. They do very little to address real barriers, and in some cases, they exist more to make agencies look good than to drive meaningful change.

But Peters and Trump aren’t arguing that DEI needs to be fixed—they’re arguing that it needs to be destroyed. That’s where we completely diverge. The idea that DEI has “gone too far” is absurd in a country where public sector leadership is still overwhelmingly Pākehā. It hasn’t gone too far; it hasn’t gone far enough.

After years of diversity reports, DEI initiatives, and public service commitments, what do we actually have to show for it at a leadership level? Nearly 90% of senior public sector leaders are still Pākehā. So while government agencies proudly announce their diversity strategies, the informal, unspoken barriers remain untouched.

The real problem isn’t a lack of DEI policies—it’s that they serve as a smokescreen. They allow agencies to claim they’re doing the work without ever having to confront the institutional biases and systemic discrimination that persist within their walls. The mere existence of a DEI framework shuts down conversations about racism and discrimination, because agencies can simply point to their policy and say, "Look, we care about diversity!" while continuing to hire, promote, and retain the same homogenous leadership teams.

My research showed that formal mechanisms to promote diversity exist, but they fail to address the informal barriers that keep diverse candidates from rising through the ranks. The public service rewards familiarity and punishes difference. Its leadership structures are built on institutional norms that resist change, not because of overt racism or sexism in most cases, but because of a deep, unspoken preference for “cultural fit” and risk aversion.

This is why diversity in leadership matters. Not because representation is some feel-good goal, or even a silver bullet, but because the perspectives of those who have historically been excluded are essential to making fairer, better decisions.

I don’t want performative DEI policies that let bureaucrats pat themselves on the back. I want real, structural change that actually removes barriers to leadership. If DEI policies exist only to create the illusion of progress, then they are worse than useless—they are part of the problem.

Fixing the System

The first step in fixing anything is acknowledging that it’s broken.

We can’t keep pretending that DEI policies are working when they’re not. And we can’t pretend that giving politicians longer terms will fix inefficiency when the real problem is a lack of meaningful accountability—at every level of government.

If we’re serious about improving leadership, governance, and public trust, we need real and transparent consequences for poor leadership, not just in Parliament but in the wider public service. We need external oversight mechanisms that actually have teeth—not just internal reviews that quietly smooth things over.

We can’t fix government inefficiency by giving politicians longer terms. And we can’t fix institutional discrimination by gutting DEI policies or pretending they’re working when they’re not.

If we want a public service that actually serves all New Zealanders, accountability—real accountability—has to come first.

Subtle, often unconscious biases and systemic barriers that persist despite formal policies promoting diversity and inclusion. Unlike overt, legally sanctioned discrimination of the past, modern discrimination operates through informal power structures, cultural norms, and implicit biases that favor in-groups while disadvantaging out-groups. This can manifest in hiring practices, leadership selection, and workplace culture, where 'cultural fit' and risk aversion serve as coded language for exclusion.

Hi Nat, I’m right with you on the need for strong accountability mechanisms—not just in government but in all organizations. Looking at you, @James Downey! What matters is competence. Without it, accountability turns into bureaucratic box-ticking instead of something that actually ensures good decision-making and performance. The question is, how? (By the way, I wish I had the beginnings of a clue.)

On diversity, I’d push back gently on a fixation with demographic categories. Diversity of ideas—among competent people—is what really drives innovation and resilience. A team of varied ethnicities and genders that all think the same way isn’t actually diverse in any meaningful sense. For example, is an internally coherent elite minority that pushes for a unified framework of Treaty and DI issues actually ‘diverse’, in the face of, and despite the existence of, widely supported alternative views?

Then there’s unconscious bias training—an industry that took off before anyone checked whether its foundations were solid. The Implicit Association Test (IAT), which underpins much of it, has been called into question for its reliability and predictive power. It’s part of the broader “replication crisis” in psychology, where landmark studies—including those on ‘implicit bias’ and ‘priming’ and the like—turned out to be … not so replicable after all. By the time the failure was acknowledged unconscious bias was off to the races, embraced by critical theorists, and had morphed into a billion-dollar industry with a life of its own.

So yes—accountability matters, competence matters, and if we’re going to talk about bias, let’s make sure the frameworks we use hold up to scrutiny.

p.s. Do you have a copy of your Masters thesis online? I’d really like to read it. This is an important topic. Did you get a chance to include empirical research in it? Your own or as citations.

Hi Natalie, thanks again for another good commentary. When I read your article on political accountability I immediately thought that it could also be applied to the public service - and beyond. Local bodies and big business exhibits the same malaise. Having dealt with public servants at both levels it’s apparent that talking the talk has very little substance when it comes to any kind of walking.

It quickly becomes obvious that the “Peter Principle” is rampant with incompetence on display at all levels.

It also appears that big business is afflicted. The CEO of Spark remains in her job despite presiding over a billion dollars loss in share value.

I disagree that failure of DEI measures is the core issue. After 75 years in all sorts of situations I would say it comes down to the quality of people. I’ve worked with and for some brilliant people and some drongos. Among the brilliant there were quite a few with little formal education. You can try and cultivate and train good leaders but you can’t regulate for it.

It is also apparent to me that in larger organisations the people at the top promote people with similar personalities. That might support your DEI concern but personality crosses racial and gender boundaries.

I wonder if we are the victims of our culture and being a small community. We tend to avoid confrontation and we don’t like to rock the boat or get offside with those around us. Robert McCulloch rails against the appointment of “mates” to senior public positions and to boards. Perhaps we’re too attached to being nice?