Tamatha Paul and Winston Peters Case Study—the Boundary of Empathy

By using Tam and Winston as examples, I hypothesise and explore a different way of thinking about our division and how our policy environment needs a rethink.

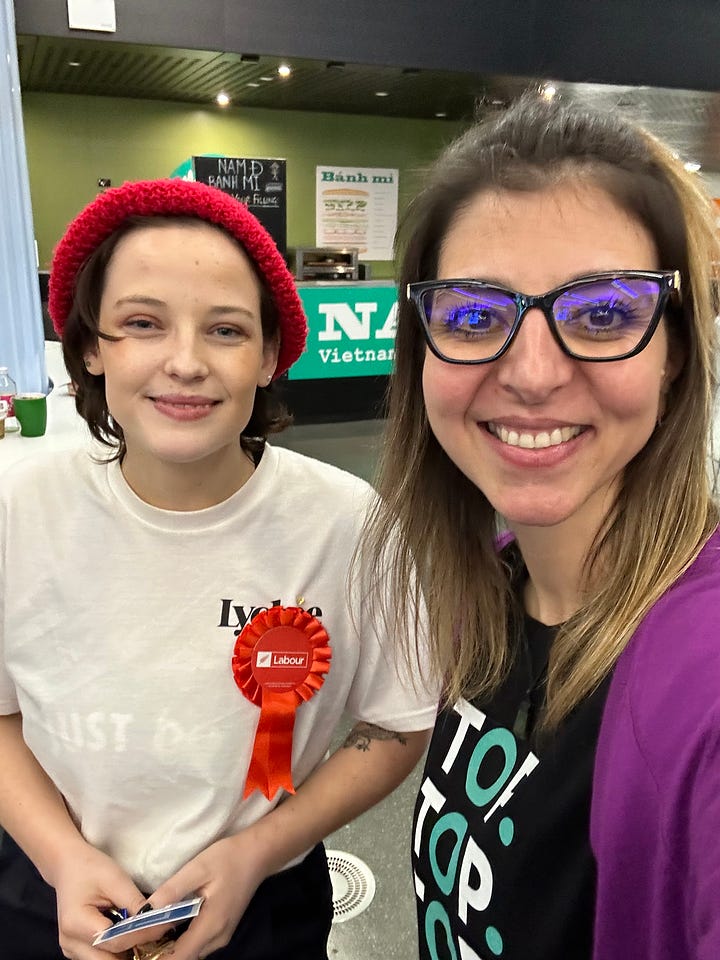

Tamatha Paul (Green Party MP) and Winston Peters (NZFirst Party Leader) have nothing in common, which seems straightforward, right? As obvious as this statement seems, there is something about it that, if thought differently, doesn’t really make sense when thinking about our policy environment.

Below, I will explore:

The illusion of division: how are we really divided?

Moving past the binary of division: our divisions are messy and our policy settings could be designed differently

The boundary of empathy: our empathy is conditional and it starts and ends with our ideological beliefs

The Illusion of Division

It's common to believe that our political divisions are the most severe and dangerous in history. This is not true for what it’s worth; we have been divided for centuries across most cultures for various issues. Protestants and Catholics, rich and poor, pro-war and anti-war, Spanish and Aztecs, Incas and Mayas, Spanish and Portuguese, English and French, French and Canadians, Māori and English, men and women, religion and science, whites and blacks, nationals and immigrants, pro-choice and pro-life, sexuality, welfare, unions, and the list goes on. So given our vast collective historical experience with social divisions, are we thinking about our current divisions in the right way? What is different about how we are divided today vs. 100, 50, or 20 years ago? And do our policies divide us more?

In politics, it seems almost obvious to organise our political parties mainly by ideological beliefs, and thanks to decades of civil rights movements around the world, we now have more diversity within these parties and more gender and ethnic representation in Parliament than ever before. So why does it all feel so chaotic? What do we need to rethink? What does this mean for how we design and develop policy moving forward?

Because our global context has shifted more in the past 10 years than it did in the previous 50 or 100 years. So the need for out-of-the-box thinking is critical. For example, if we vote based on ideological belief, why then do we try and make policies for groups based on other attributes such as ethnicity, age, gender, and nationality? Maybe now that we have achieved such success in political representation, we need to review our policy settings because the way we are doing it now is proving to be a shitshow.

So let’s hypothesise. What if we need to find ways to develop policies that unify groups based on ideologies and not ethnicity, race, nationality, or culture? Some research1 suggests that ideological and moral alliances, like those between progressives and liberals, create more significant commonalities and divisions than race, age, gender, or nationality. For instance, a progressive/liberal Māori (Tamatha Paul) might find it hard to unite with a conservative/nationalistic Māori (Winston Peters) and easier to unite with a progressive/liberal Pākeha (James Shaw).

So if Tam and Winston were not politicians and were members of the general population, the government would make assumptions about them based on the fact that they are both urban, well educated, and high-income earning Māori and therefore need the same policy solutions. The fact that Tam and Winston are both Māori doesn’t mean they can find empathy or common ground to work together, and it’s unlikely they will. So why are we expecting anybody else to think like that? We are currently organising our population into groups based largely on ethnicity, nationality, gender, and age, while our politicians, and therefore their objectives, are organised based on moral and political ideology.

Now, I’m not questioning representation or assuming that because we are all one nationality, we will agree, but if you think about it, the way we develop policy does assume that all ethnicities have the same problems and therefore need the same solutions. For example, we have a Ministry for Māori Development, a Ministry for Pacific, and a Ministry for Ethnic Communities. However, given that we seem to be “binded and blinded”2 by our moral ideologies and less by ethnicity and race, why don’t we then have a Ministry for Liberals and a Ministry for Conservatives? Indulge me…

To be clear, I am not suggesting we establish a Ministry for Conservatives and a Ministry for Liberals, but I am suggesting that we try to think about how we can achieve some civics, policy, and political consensus about key policy topics like housing, tax, and welfare differently. Our current policy environment is dividing us more and more; it just isn’t working. This is true for both left and right governments. Nobody is getting this right.

Aiming to cater to policies for all nationalities, languages, races, and ethnicities is financially, logistically, ideologically, and practically impossible. However, the government keeps trying to do that (like the last Labour government) or trying explicitly to not do that (like our current government), repeatedly failing and lowering our trust in government. We are in a losing policy spiral. When we find policy solutions for groups based on race, ethnicity, and nationality, it seems not only impossible but very complex, painful, and useless to design, develop, and implement.

The policy narrative of diversity and inclusion, multiculturalism, and biculturalism are all equally problematic. It puts the focus on groups based on attributes that don’t actually unite us at all. So the intersectional side of it will always get in the way. Developing policy and thinking that it will create a just and united New Zealand based on race, culture, and ethnicity is a myth, unhelpful, and painful; creating a policy where all Māori benefit or agree, or all Pacific benefit or agree, or all Migrants benefit or agree is impossible because we are not wired to coexist like that.

For example, if I'm a Mexican migrant, does that mean I have anything in common with other Mexican migrants from Latin America in New Zealand? Unlikely. So its fair to assume that policies like the Employment Action Plan by the Ministry of Ethnic Communities, aimed at helping all ethnic communities, will work. It won’t. It seems like the cultural tail is wagging the ideological dog, and there is no algorithm for deciding how to adjudicate between them.

To make things worse and more messy, when there's a lack of alignment in ideological beliefs and it collides with people's differences in nationality or race, we are quick to call it xenophobia or racism when, in reality, the person is neither; they don’t agree with your ideological beliefs; and the optics are then racism and xenophobia. Which compounds and worsens the current policy shitshow, further reducing our trust in governments and ourselves.

Beyond Binary Divisions

If Tam and Winston examine the same evidence and information, they are likely to draw divergent conclusions. The moral chasm separating them outweighs their common ground, influencing their ability to interpret, formulate, and contemplate policy. This raises the question: Are the general public any different?

Emotions and common sentiments frequently have a greater influence on our perspectives and convictions than facts and logic. This model posits that to effectively engage with and sway others' moral perspectives, one must address underlying intuitions rather than rely solely on logical arguments, evidence, or facts. Consequently, our moral ideologies both blind and bind us, transcending race, ethnicity, and nationality. While acknowledging the influence of culture on our sentiments and ideologies, it's crucial to reflect on whether our current policy frameworks need reevaluation.

Considering the advancements in political representation over the past decades, it prompts us to reassess our policy settings to ensure genuine enhancements in people's quality of life and prevent further divisions. The evolution of affirmative action and representation politics underscores the complexity of group dynamics. Notably, diversity within groups like women, migrants, and Māori highlights the diversity of opinions within these communities. Conversely, there tends to be more alignment among conservatives or liberals, irrespective of their cultural background.

The discrepancy between ideological divisions in politics and policies designed to cater to specific ethnic, racial, or national groups raises a pertinent query: Why do such divisions persist? This observation prompts a critical examination of the alignment between political ideologies and policy frameworks aimed at serving diverse demographics.

The Boundary of Empathy

Talking about our political views is so hard, and to stop being so polarised and stressed about it, we keep hearing that we should be more empathetic, put ourselves in other shoes, listen to understand, and not respond, right? However, we wouldn't expect Tam and Winston to do that. Not only would we not expect them to do that, but if their voting base saw them attempting to find common ground, Tam and Winston would quickly lose political capital. Its like publicly showing cross-party solidarity is naive at best and political suicide at worst.

Empathy is conditional, and it’s conditional to our moral ideologies, not to the racial or ethnic group we belong to. The challenge we face is bridging the gap of empathy and understanding across moral and ideological divides; it’s not Māori vs. Pākeha, rural vs. urban, or nationals vs. immigrants. Empathising with those who share our values regardless of race, nationality, or ethnicity is straightforward. For instance, a New Zealand-born citizen might find it easier to empathise with overseas-born citizens who share similar ideologies than those who don't.

True empathy is put to the test when it encounters opposing moral beliefs. In such cases, emotional reactions can dominate and disrupt logical discourse, leading to polarised debates where compromise is elusive and understanding is scarce. In these moments, we may justify our lack of empathy by becoming more entrenched and aggressive in defending our positions and drawing lines dividing us by 'us' versus 'them,' irrespective of nationality, race, or ethnicity. This trickles into our policy design in obscure and mysterious ways, creating a dramatic swing between the Left and the Right. Bring on my argument for the need for a center (Blue/Green) party!

So Tam and Winston have nothing in common; we can agree on that. So can we stop assuming that our policies should be designed so all ethnic and cultural groups fit into a tiny policy box? How we do this, I don’t know, but again, I think its a string worth pulling.

There are a lot of academic papers and books that discuss this, but one standout for me at the moment is: Berger, P. L. (1998). The limits of social cohesion : conflict and mediation in pluralist societies : a report of the Bertelsmann Foundation to the Club of Rome. Westview Press.

Haidt, J. (2012) The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion

I would hope that many of us would find the time slowly and carefully to read and absorb this very well thought through article.

Had to subscribe (again) as I love your articles. Very thoughtful and so different from the usual “angernomics” articles we are normally bombarded with.