Let's talk about corruption in New Zealand

There is a difference between incompetence and corruption, and there is a difference in individual corruption and systemic corruption. These distinctions matter.

As conversations about corruption in government resurface, it's paramount to scrutinize New Zealand's reputation as one of the least corrupt nations globally.

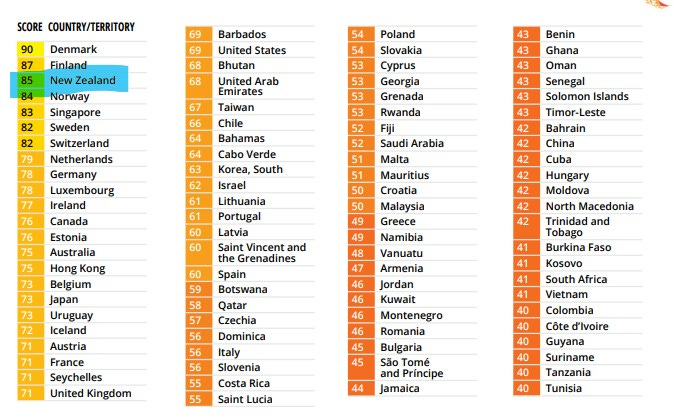

Hailing from Mexico, where Mexico sits squarely in the middle of the corruption spectrum (as shown in the tables below from the Corruption Perception Index 2023), I know a thing or two about what it's like to live in a country where you can’t trust your cops, your government agencies, your justice system or your politicians.

To think that Mexico is in the middle of the corruption pack (126 out of 180 countries), I can't even imagine the thought of life in a nation entrenched at the bottom of that scale like Somalia or Iran). It is chilling.

In a recent analysis, Bryce Edwards delves into the integrity issues of the previous government, highlighting the need for higher standards in the Beehive. He argues that Luxon must declare war on corruption, cronyism, and low standards, setting a new precedent.

This article seeks to build upon Edwards' insights and contribute to the ongoing discourse surrounding corruption in New Zealand.

First and foremost, it's essential to differentiate between corruption and incompetence and individual versus systemic corruption. We often observe incompetence rather than systemic corruption in New Zealand. But discuss and report it as though it was an implied systemic corruption. This is unhelpful and needlessly alarmist.

Instances of politicians or public servants faltering in their duties may lead to swift accusations of corruption from the media1 and analysts.

This knee-jerk reaction is problematic, fostering unnecessary fear and distrust in our institutions. I would like it if, when discussing corruption, we could be specific if it's an individual doing something intentionally to game the system (individual corruption) to benefit themselves or just having a huge lapse of judgment (incompetence). So my question is: is it increased systemic corruption or just increased reporting of corruption as a political strategy to undermine opponents? Two very different things.

Following the Hager (2014) revelation about the Key government's two-faced media strategy post-2008, there's been a rising awareness in New Zealand about how corruption scandals are used as political tools.

Particularly, there's a trend of launching allegations of misconduct against political opponents, often starting on social media (Zirker and Barrett 2017). This kind of political maneuvering seems to be happening more and more in various countries (Lowi 1988). With political rivalry increasingly leaning on these tactics, expecting spikes in corruption scandals during pivotal moments like elections or government formations is reasonable.2

Corruption possesses the potential to skew government objectives and impede the maximization of public services, serving as the insidious grease lubricating the wheels of a rigid and incompetent administration. Is this what New Zealand is talking about when we discuss corruption?

Identifying and measuring corruption presents a significant challenge due to its clandestine nature. Research indicates that corruption thrives in environments sheltered from foreign competition, with limited economic and press freedoms. Conversely, countries with active female participation in the economy and government tend to exhibit lower levels of corruption3.

More locally, despite New Zealand's relatively low corruption levels, it grapples with a dark history concerning Māori. Much of Māori land confiscation was legitimized for illegitimate purposes, and successive governments failed to honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi, signed in 1840. This historical context often gets overlooked in academic analyses of corruption in New Zealand, but its impact persists to this day.

Today, there are several initiatives aimed at preventing systemic corruption within New Zealand public institutions. For instance, the International Anti-Corruption Coordination Centre (IACCC) was established in 2017, along with resources like "Saying No to Bribery and Corruption – A Guide for New Zealand Businesses" developed by the Ministry of Justice.

While New Zealand remains solidly atop the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), it's essential to note that major corruption incidents akin to those in Australia, the USA and the UK have not surfaced here. However, gaps in political integrity oversight persist, particularly concerning Parliament, political party funding, lobbying regulation and Ministers overstepping or using their role to share information that can rig the system. Individual and institutional incompetence is always a gateway for actual systemic corruption to creep in.

Addressing these issues requires independent, comprehensive, and future-focused corruption prevention mechanisms. Whether through establishing an anti-corruption agency or by further funding and empowering existing agencies, proactive measures are crucial to safeguarding our institutions and upholding the principles of transparency and integrity that define New Zealand's governance.

The Opportunities Party campaigned for an anti-corruption commission, advocating for greater oversight over political donations to bolster public trust in our officials. Recent revelations surrounding Labour MP Kiri Allan's donations or John Tamihere, the president of Te Pati Māori, is also the Chief Executive of the Waipareira Trust charity, raises concerns about how much the two organisations overlap and the legality of funding that is given by the charity to Tamihere’s political campaigns underscore the importance of maintaining political neutrality among public officials.

Let's not shy away from confronting corruption. Still, let's ensure our discussions are grounded in facts, nuance and context, steering clear of unnecessary panic and mistrust.

Together, we can work towards a more transparent and accountable political landscape in New Zealand because our strongest weapon against systemic corruption is prevention.

Carlo Berti (2019) Rotten Apples or Rotten System? Media Framing of Political Corruption in New Zealand and Italy, Journalism Studies, 20:11, 1580-1597

Patrick Barrett, & Daniel Zirker. (2016). Corruption scandals, scandal clusters and contemporary politics in New Zealand: Corruption scandals in New Zealand. International Social Science Journal, 66, 229–240.

Salinas Occelli, C. E. (2005). Political and social roots of economic vices and virtues: Evidence from Mexico. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.