Another perspective of Te Tiriti o Waitangi: The relationship between biculturalism and multiculturalism

How can we talk if Te Tiriti o Waitangi is not clear if we must accept that it is clear? And how do we discuss it in a respectful, humble, and educated way? I am still unsure about this.

In this article, I will share:

My personal journey as a Mexican migrant, tauiwi of colour and my understanding of te Tiriti o Waitangi.

How our public institutions grapple with the reconciliation between biculturalism and multiculturalism.

I share some resources if you want to read further.

My individual journey with te Tiriti o Waitangi

There is a term in Latin American culture that has guided me through my journey in Aotearoa: mestiza1. This term means that we are the colonizers and the colonized; it describes living in an ambiguous world of mixed and contradictory identity. So, when I moved to Aotearoa 13 years ago, I started a journey to understand my role within Te Tiriti o Waitangi as somebody who isn't a colonizer or a colonized but both. I wanted to understand what my role as Tangata Titirti and tauiwi of colour meant and how it relates to my being a Mexican woman and a citizen of Aotearoa. I have studied te reo Māori, studied New Zealand and Māori history at length, familiarized myself with different tikanga, perspectives, and taken every single Te Tiriti o Waitangi course and workshop available in Wellington to help me upskill my intellectual and historical understanding.

And after this journey, I can safely say I find it all really, really hard.

For example, I don’t know where I whakapapa back to and I don’t like talking or thinking about it. I don’t know my dad, and my mother didn’t speak much about where she came from. I only met one grandparent who died when I was 10, and I never got along with her. I am not close to my family and actually have a painful relationship with the idea of whanau and community.

I struggle with the idea of Turangawaewae, place, home, and land. I have lived in over five countries and feel like I have values from all of them and belong to none of them. I find thinking about these things very painful and don’t want to do it. So, how do I reconcile my role as Tauiwi of colour and Tangata Titiriti with my individual past, values and preferences? I’m not entirely sure.

Yet, amid these complexities, I find solace in the shared human experience of grappling with social integration. It is a journey of self-discovery that we all navigate, and it prompts us to reflect on our individual pasts, values, and preferences while embracing the differences in our interconnected world.

Here is a list of most of the workshops I have attended or used their resources to upskill that have helped me a great deal:

Groundwork - Introduction to Te Tirirti o Waitangi - one of the first I took like ten years ago

Tauiwi Toutoko - I have used and read most of their resources

The Wall Walk - a course I took more recently, and that was incredible

I share this context to highlight how I struggle with Te Tiriti o Waitangi and to place myself within the discussion. I come to it with respect, humility, and honesty, and I hope it is read in that spirit.

Now, that is my own personal perspective. So how does the New Zealand Public Service deal with it? That isn't very clear if you read most of their diversity and inclusion policies. The New Zealand government doesn’t quite understand its role as a partner with Tangata Whenua.

Biculturalism vs. Multiculturalism: A Government Conundrum

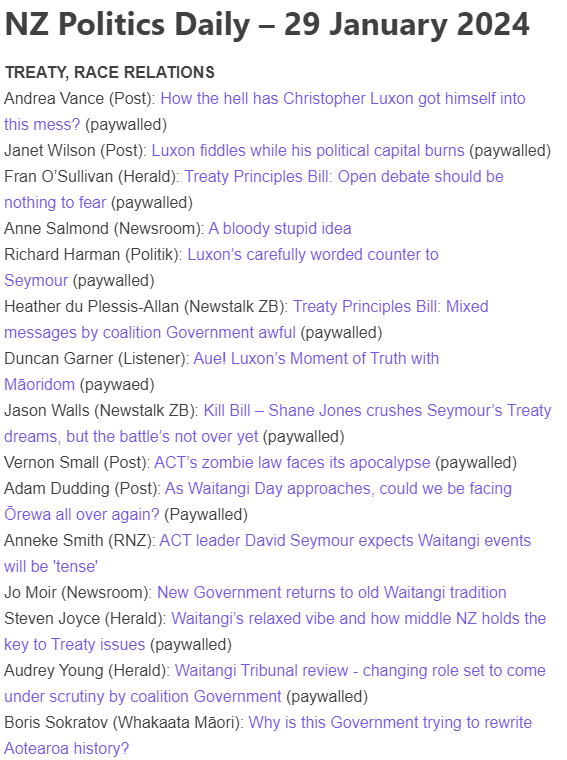

New Zealand has long grappled with the relationship and reconciliation between the Crown and Te Tiriti o Waitangi. This foundational document forms the backbone of the relationship between Māori and the Crown. Our new New Zealand government has taken steps to redefine the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, sparking intense debates across the country. Below is a screenshot of

newsletter NZ Politics Daily for yesterday (29 January 2024) showcasing a few of the articles being published discussing this topic.So, the New Zealand Public Service has a very formal and overt bicultural framework that is evident across many policies. In this current bicultural framework, the role and value of migrants is murky; even though clear to some groups, it is not clear to the government, and this was obvious in the over 1,500 pages of government documents I reviewed over the past three years for my master’s thesis on how to diversity leadership in the New Zealand public service.

The New Zealand government often blurs the lines between its bicultural and multicultural frameworks within its written policies. There's a distinct struggle within the Public Service to differentiate its responsibilities under Te Tiriti o Waitangi from those under the Human Rights Act, the Public Service Act, or its legislation2. Even ideas like public servants paying or receiving koha are complex to figure out within the government because they vary from agency to agency.

For example, the Human Rights Commission in New Zealand has a very clear description of what the relationship between human rights and Te Tiriti o Waitangi is:

The Treaty of Waitangi is New Zealand’s own unique statement of human rights. It includes both universal human rights and Indigenous rights. It belongs to and is a source of rights for, all New Zealanders.

However, the policies I reviewed did not mention this connection or how it all links together.

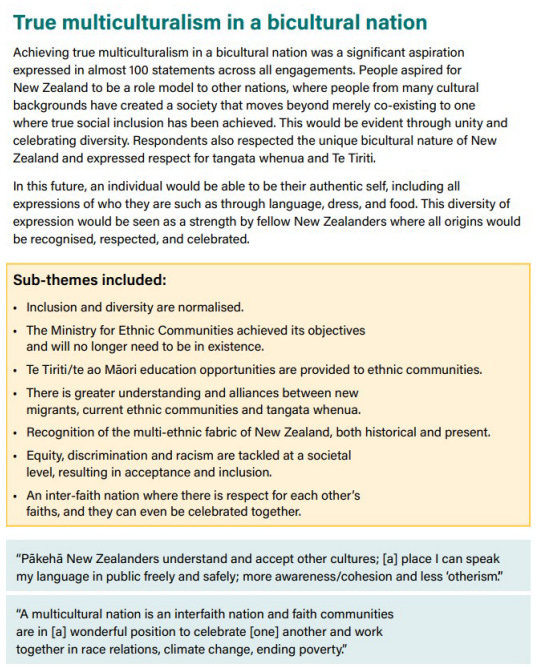

Below is a screenshot of a report published by the Ministry for Ethnic Communities last year to describe the relationship between ethnic communities and Māori in Aotearoa

Need for clarity is not new

Linda Tuhiwai Smith states this struggle perfectly in her book Decolonizing methodologies:

… our collective memory of imperialism has been perpetuated through the ways in which knowledge about Indigenous peoples was collected, classified and then represented in various ways back to the West, and then, through the eyes of the West, back to those who have been colonized. Edward Said refers to this process as a Western discourse about the Other which is supported by ‘institutions, vocabulary, scholarship, imagery, doctrines, even colonial bureaucracies and colonial styles.

While the approach and language used by some political figures may not be endorsed by all, I think there is some need for the government and its employees to have more clarity on what Te Tiriti o Waitangi means, especially in their formal policies.

For example, when the government says it has or will engage with Māori, it is unclear what level of engagement they are doing, is it informing, partnering or consulting? These three different types of engagement carry substantially different assumptions, costs and results. So when a cabinet paper says it has engaged with Māori, it can mean that the government agency sent a letter to an iwi that they might or might not gotten to fulfil the legislative mandate to inform them, all the way to a partnership model like the Mana Ōrite Relationship Agreement between Data Iwi Leaders Group and Stats NZ that was signed on 30 October 2019.

Biculturalism and multiculturalism: a closer look

Biculturalism implies two peoples. Many researchers stating that there are Māori and non-Māori, though it is a bit more complex than that over simplification. New Zealand demographics' show that there is clearly more than two peoples. Which is where the conflict between biculturalism and multiculturalism lies.

Biculturalism in New Zealand revolves around four primary objectives:

Recognizing Distinct Ideas and Institutions: Acknowledging the unique ideas and institutions of both Māori and the Crown.

Inclusivity for Māori: Making public institutions more inclusive for Māori as Treaty partners.

Engagement with Māori: Enabling better engagement between the government and Māori as tangata whenua and citizens.

Representation and Identity: Granting Māori representation in parliamentary seats, promoting land claim settlements, and blending elements of both Pākehā and Māori identities for a stronger national identity.

The relationship between the Public Service and Te Tiriti o Waitangi has faced its share of challenges:

The government's failure to consult with Māori about immigration laws and policies.

Concerns that multiculturalism might displace the concept of biculturalism.

The Public Service must recognize Māori as partners, which would involve transferring power to Māori, iwi, and communities.

Multiculturalism: A Counterpoint

Multiculturalism in New Zealand pursues different objectives, at times seemingly conflicting with biculturalism:

It aims to develop group-differentiated policies beyond individual rights.

Multiculturalism supports group rights to secure a cultural context, which might be seen as contrasting with the individual autonomy promoted by liberal multiculturalism.

Critiques of Multiculturalism

The link between autonomy and group respect.

Confusion surrounding terms like ethnicity, race, nationality, culture, identity, and diversity and inclusion (D&I).

The practical challenges of accommodating various cultures, languages, and groups within the Public Service's constraints.

Balancing Act: Navigating the Intersection

The debate over whether biculturalism and multiculturalism clash or complement each other continues. Some argue they can coexist and complement each other, while others view them as mutually exclusive. The complexity arises when attempting to reconcile these frameworks with the pursuit of equality.

The Evolving Government Approach

Recent developments have stirred the pot. A leaked Ministry of Justice document unveils plans to rewrite the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, particularly regarding the "Treaty Principles Bill." This proposal has ignited controversy as it seeks to redefine crucial Treaty principles, including extending chieftainship rights to all New Zealanders.

The relationship between biculturalism, multiculturalism, and Te Tiriti o Waitangi is intricate, and the New Zealand government's evolving approach adds a new layer of discussion. Balancing the rights and representation of Māori with the diverse cultural landscape of New Zealand is an ongoing challenge with no easy answers. The future promises continued debates and negotiations, shaping the nation's identity and policies.

Additional reading recommendations:

Thanks for reading this far and for subscribing, liking and sharing. See you next Tuesday!

The term mestizo means mixed in Spanish and is generally used throughout Latin America and some Southeast countries to describe people of mixed ancestry with a white European and an indigenous background.

New Treaty New Tradition | Reconciling New Zealand and Māori Law is a great book that talks about this tension in depth.

thank you for writing this, it is helping me on my journey of understanding Te Tiriti. I was wondering if you would be interested in writing more about each of the articles and what you think they say, and what they would look like actualised. I am collecting a diverse range of understandings about each article and would love to read yours!

Interesting thoughts Natalia. There is more shadow than light in the position of those opposing the Act Bill in my view. Specifically, there are two narratives: partnership (co-governance) and two sovereignties (beyond the partnership principle). I'm trying to get someone authoritative to say how or if they reconcile, as I can't see that they do. And then you add article three: if there are two sovereignties and/or partnership how can the Crown assume responsibility for equity of outcomes, since it doesn't 'control' all the 'levers'? I think the public deserves to know exactly what tangata whenua think te Tiriti actualised looks like, so we can have informed discussion. Any thoughts? Best, David King