Housing Affordability – What Does it Even Mean?

Why Housing Affordability Isn’t as Simple as It Sounds

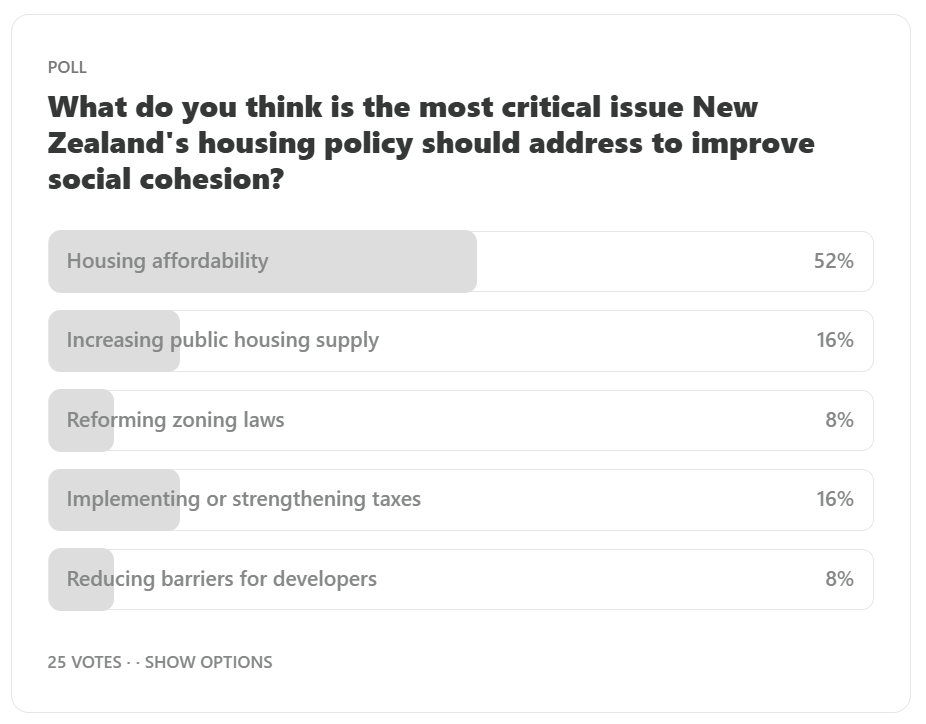

A few weeks ago, I wrote about housing policy and social cohesion in Less Certain. I ran a poll asking what you thought had the most significant impact on social cohesion: housing affordability, increasing housing supply, reforming zoning laws, reducing barriers for developers, or strengthening relevant taxes like capital gains, land, or wealth tax.

A whopping 52% of you said housing affordability was the most important. So, let’s dive into it.

So, I thought I would expand on this. In this article, I will focus on unpacking the definition of housing affordability. A quick caveat: I know some would argue that it's as simple as supply and demand: We need more houses to meet the demand of people wanting a home. However, I have learnt that it's actually not that binary, simple, or easy to understand. There are different housing metrics and terms that, to the average person, a.ka. me, don’t mean much.

First, can we confidently say we understand what “housing affordability” even means? Most of us assume it just means everyone should be able to afford a house. Sounds simple, right? But how do we measure what’s affordable? Is it affordable in relation to your income? The housing market? Which market rate? Auckland, Wellington, the Reserve Bank, other banks? What prices were ten years ago when your parents told you to "just save"?

It turns out that defining housing affordability is way more complicated than we think, and I bet most of us have no clue how it’s defined, let alone measured. (I didn’t know or understand these ideas or questions either until I started researching this.)

So, let’s unpack this.

What Is Housing Affordability?

Housing affordability refers to the cost of housing relative to your income and whether you can pay for it. It sounds straightforward, but there’s always more to it. Here’s a quick breakdown:

Cost relative to income: Housing costs should generally not exceed 30% of your gross household income. If you’ve ever felt like your rent or mortgage is eating up your paycheck, this might explain why.

Ability to purchase: This includes the price-to-income ratio—how many years of your salary would it take to buy a house? Don’t forget the mythical deposit we’re all supposed to save for while eating and paying bills.

Rental affordability: For folks not on the property ladder, this measures whether rent leaves them with enough left over to live—which, in many cases, not so much.

Quality and suitability: Affordable housing should also meet your basic needs in size, quality, and location. After all, no one dreams of living in a shoebox, an hour away from where they live or, even worse, away from their family, community, or health and education services, even if they can afford it.

How Do We Measure Housing Affordability?

Different countries measure affordability in various ways, which makes sense because this issue is complex. Here’s how they do it:

Housing cost to income ratio: What percentage of your income goes to housing? If it’s more than 30%, you’re “overburdened”—a fancy way of saying you are paying more than you have.

House price to income ratio: Median house price divided by median income. The bigger the number, the harder it is to buy a home. Simple, right?

Residual income approach: How much money do you have left after paying for housing? If your answer is insufficient for food and essential services, your house is too expensive.

Affordability indices combine house prices, incomes, and interest rates into one handy figure. But don’t get too excited—the numbers aren’t exactly uplifting.

How Do Different Countries Measure Affordability?

Now, let’s get global. Every country has its way of figuring out if housing is affordable. Here’s the rundown:

New Zealand: In Aotearoa, the Ministry of Housing uses the “Change in Housing Affordability Indicators” (CHAI). It tracks rent prices vs. income, how hard it is to save for a deposit, and whether you can afford your mortgage.

OECD Countries: The OECD checks how much low-income households spend on housing. If it’s more than 40%, they sound the alarm, which, to surprise to none, they already are because housing affordability issues are not just a problem here but in most OECD countries.

United States: The 30% rule is still king in the U.S. If you’re spending more than 30% of your income on housing, you’re in trouble (and most people are far past that point). They even break it down by income level and household size—ensuring no one feels left out of the affordability crisis.

Australia and Canada: These two rank among the least affordable places to live. Sydney and Toronto? Beautiful cities—just don’t expect to own a home anytime soon unless you’ve got a winning lottery ticket.

World’s Least Affordable Housing Markets

Here’s where housing is so unaffordable you might want to start saving for a house… on another planet:

Hong Kong (China): Price-to-income ratio of 16.7. Translation: You’ll need 16 years of saving every penny to buy a home.

Sydney (Australia): At 13.8, Sydney has sunny skies and empty wallets.

Vancouver (Canada): With a ratio of 12.3, enjoy the stunning views—because you will be paying for the mortgage most of your lives.

Auckland (New Zealand): With a ratio of 8.2, Auckland is a bargain compared to the others. Still, good luck with that deposit.

The Housing Paradox: Affordability, Sustainability, and Quality—Can We Have All Three?

We all want affordable housing, but we also want it to be sustainable and high-quality. Nobody wants to live in an eco-friendly cardboard box.

Here’s the catch: balancing affordability, sustainability, and quality is like juggling flaming torches. Want your house to be affordable? Then sustainability might take a back seat. Want it to be sustainable? Get ready for some serious upfront costs. It’s a never-ending cycle. This rubric cube of three colours is a very hard nut to crack.

Affordability vs. Sustainability: Eco-friendly homes tend to cost more. Sure, they save you money long-term, but that upfront cost is out of reach for many.

Quality vs. Affordability: Cheaper homes usually mean cutting back on quality. Smaller spaces, lower-quality materials, and sometimes not-so-great neighbourhoods—sound familiar?

Sustainability vs. Quality: Sustainable homes often require top-notch materials, which means… yep, higher prices.

Like most OECD countries, New Zealand is caught in this cycle. We want affordable homes, but many new builds don’t meet the sustainability or quality standards we need. And the ones that do? Let’s say they’re out of reach for most first-time buyers.

So what’s the answer? I have no idea. I'm just starting to wrap my head around the landscape, the players, and understanding all these terms. What I have reflected on is if I struggle to map, understand, and identify all these different issues, terms, and components, who is somebody who is doing this full-time as a part of my PhD? I can't even imagine how complex it is for most people to get their heads around.

As I keep developing my ideas and theories and discovering more about this topic, I'll keep sharing, but I would love to hear your thoughts about his issue.

Catch ya next week!

Affordability, sustainability and quality are certainly 3 factors that can be considered. I live in South Auckland. Around here affordability trumps the other two. An affordable non-sustainable pigeon coop beats a car or a relative’s garage any day.

On one side of the affordability equation there are incomes. So an economy with jobs that lift incomes would be a good start.

The other side of affordability is cost - and in cost I would include location with respect to public transport, jobs, schools, medical support and shops. (‘Desirability’ of location doesn’t rate. There is nothing wrong with Māngere Pak’nSave.)

Reducing cost means bringing down the cost of land adjacent to the above. This is an issue of reducing zoning restrictions. It also means reducing the cost of building, which mainly means increasing competition in the building materials market, but not forgetting the training for tradies.

I don’t know where it is at, but Auckland’s long term plan is onto it - significantly loosen zoning restrictions along transport routes and especially near hubs like Onehunga, Avondale or Manukau.

Affordability is tops. I think the correct troika of concerns is the economy, zoning restrictions and building sector competition. What’s more, these don’t involve tradeoffs one against the others.